J.C. Ryle (1816-1900)

J.C. Ryle was an English evangelical and the first Anglican bishop of Liverpool. In the following excert from his commentaries, he addresses the question of whether the account of the woman caught in adultery should be accepted as authentic.

Short answer: “In cases of doubt like this, it is wise to be on the safe side. On the whole I think it safest to regard this disputed passage as genuine. At any rate, I prefer the difficulties on this side to those on the other.”

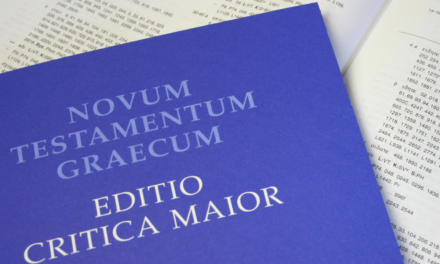

These eleven verses [John 8:1-11], together with the last verse of the preceding chapter, form perhaps the gravest critical difficulty in the New Testament. Their genuineness is disputed.

It is held by many learned Christian writers—who have an undoubted right to be heard on such matters—that the passage was not written by St. John, that it was written by an uninspired hand and probably at a later day, and that it has no lawful claim to be regarded as a part of canonical Scripture.

It is held by others—whose opinions, to say the least, are equally entitled to respect—that the passage is a genuine part of St. John’s Gospel, and that the arguments against it, however weighty they may appear, are insufficient and admit of an answer. A summary of the whole case is all that I shall attempt to give.

In the list of those who think the passage either not genuine or at least doubtful, are the following names: Beza, Grotius, Baxter, Hammond, A. Clarke, Tittman, Tholuck, Olshausen, Hengstenberg, Tregelles, Alford, Wordsworth, Scrivener.

In the list of those who think the passage genuine, are the following names: Augustine, Ambrose, Euthymius, Rupertus, Zwingle, Calvin, Melancthon, Ecolampadius, Brentius, Bucer, Gualter, Musculus, Bullinger, Pellican, Flacius, Diodati, Chemnitius, Aretius, Piscator, Calovius, Cocceius, Toletus, Maldonatus, á Lapide, Ferus, Nifanius, Cartwright, Mayer, Trapp, Poole, Lampe, Whitby, Leigh, Doddridge, Bengel, Stier, Webster, Burgon.

Calvin is sometimes named as one of those who think the passage before us not genuine. But his language about it in his Commentary is certainly not enough to bear out the assertion. He says, “It is plain that this passage was unknown anciently to the Greek Churches; and some conjecture that it has been brought from some other place and inserted here. But as it has always been received by the Latin Churches and is found in many old Greek manuscripts and contains nothing unworthy of an Apostle, there is no reason why we should refuse to apply it to our advantage.”

The arguments against the passage are as follows:

(1) That it is not found in some of the oldest and best manuscripts, now existing, of the Greek Testament.

(2) That it is not found in some of the earlier versions or translations of the Scriptures.

(3) That it is not commented on by the Greek Fathers, Origen, Cyril, Chrysostom, and Theophylact in their expositions of St. John, nor quoted or referred to by Tertullian and Cyprian.

(4) That it differs in style from the rest of St. John’s Gospel and contains several words and forms of expression which are nowhere else used in his writings.

(5) That the moral tendency of the passage is somewhat doubtful, and that it seems to represent our Lord as palliating a heinous sin.

The arguments in favor of the passage are as follows:

(1) That it is found in many old manuscripts, if not in the very oldest and best.

(2) That it is found in the Vulgate Latin, and in the Arabic, Coptic, Persian, and Ethiopian versions.

(3) That it is commented on by Augustine in his exposition of this Gospel, while in another of his writings he expressly refers to and explains its omission from some manuscripts; that it is quoted and defended by Ambrose, referred to by Jerome, and treated as genuine in the Apostolical constitutions.

(4) That there is no proof whatever that there is any immoral tendency in the passage. Our Lord pronounced no opinion on the sin of adultery but simply declined the office of a judge.

It may seem almost presumptuous to offer any opinion on this very difficult subject. But I venture to make the following remarks and to invite the reader’s candid attention to them. I lean decidedly to the side of those who think the passage is genuine, for the following reasons:

1. The argument from manuscripts appears to me inconclusive. We possess comparatively few very ancient ones. Even of them some favor the genuineness of the passage. The same remark applies to the ancient versions. Testimony of this kind, to be conclusive, should be unanimous.

2. The argument from the Fathers seems to me more in favor of the passage than against it. On the one side, the reasons are simply negative. Certain Fathers say nothing about the passage but at the same time say nothing against it. On the other side, the reasons are positive. Men of such high authority as Augustine and Ambrose not only comment on the passage but defend it s genuineness, and assign reasons for its omission by some mistaken transcribers.

Let me add to this that the negative evidence of the Fathers who are against the passage is not nearly so weighty as it appears at first sight. Cyril of Alexandria is one. But his commentary on the eighth chapter of John is lost, and what we have was supplied by the modern hand of Jodocus Clichtovoeus, a Persian doctor, who lived in the year 1510 A.D. (See Dupin’s Eccles. hist.) Chrysostom’s commentary on John consists of popular public homilies, in which we can easily imagine that such a passage as this might possibly be omitted. Theophylact was notoriously a copier and imitator of Chrysostom. Origen, the only remaining commentator, is one whose testimony is not of first-rate value, and he has omitted many things in his exposition of St. John. The silence of Tertullian and Cyprian is perhaps accountable on the same principles by which Augustine explains the omission of the passage in some copies of this Gospel in his own time. Some, as Calovius, Maldonatus, Flacius, Aretius, and Piscator, think that Chrysostom distinctly refers to this passage in his Sixtieth Homily on John, though he passes it over in exposition.

3. The argument from alleged discrepancies between the style and language of this passage and the usual style of St. John’s writing is one which should be received with much caution. We are not dealing with an uninspired but with an inspired writer. Surely it is not too much to say that an inspired writer may occasionally use words and constructions and modes of expression which he generally does not use, and that it is no proof that he did not write a passage because he wrote it in a peculiar way.

I leave the subject here. In cases of doubt like this, it is wise to be on the safe side. On the whole I think it safest to regard this disputed passage as genuine. At any rate, I prefer the difficulties on this side to those on the other.

The whole discussion may leave in our minds, at any rate, one comfortable thought. If even in the case of this notoriously disputed passage (more controverted and doubted than any in the New Testament) so much can be said in its favor, how immensely strong is the foundation on which the whole volume of Scripture rests! If even against this passage the arguments of opponents are not conclusive, we have no reason to fear for the rest of the Bible.

After all, there is much ground for thinking that some critical difficulties have been purposely left by God’s providence in the text of the New Testament in order to prove the faith and patience of Christian people. They serve to test the humility of those to whom intellectual difficulties are a far greater cross than either doctrinal or practical ones. To such minds it is trying, but useful, discipline to find occasional passages involving knots which they cannot quite untie and problems which they cannot quite solve. Of such passages the verses before us are a striking instance. That the text of them is “a hard thing” it would be wrong to deny. But I believe our duty is not to reject it hastily, but to sit still and wait. In these matters, “he who believes shall not make haste.”

The following passage from Augustine (De conjug. Adult.) is worth notice. Having argued that it well becomes a Christian husband to be reconciled to his wife upon her repentance after adultery (because our Lord said “Neither do I condemn thee; go and sin no more”), he says: “This, however, rather shocks the minds of some weak believers—or rather unbelievers and enemies of the Christian faith—insomuch that, afraid of its giving their wives impunity of sinning, they struck out of their copies of the Gospel this that our Lord did in pardoning the woman taken in adultery; as if He granted leave of sinning when He said, “Go, and sin no more.” Augustine, be it remembered, lived about 400 A.D.

Those who wish to look further into the subject of this disputed passage will find it fully discussed by Gomarus, Bloomfield, and Wordsworth.